Istanbul Pavilion featured at the 9th Shanghai Biennale

A Twist in the Untimely

By Defne Ayas and Davide Quadrio

Istanbul and Shanghai

While talk is thick these days about a crisis in the West—be it economical, ecological, cultural or spiritual—a larger question looms: how and where to situate the rich content and intelligence of a rising China or a potent Turkey vis-à-vis a diverse European continent? More and more it seems that the West cannot prescribe itself in neat packages and solutions, while the aforementioned countries continue to be riddled by moving-target projections and contradictory positions.

Historically, Istanbul and Shanghai are two cities that have suffered most from both the conscious and subconscious anxieties produced by the West—a topic that still remains under-researched. Although there seems to be much room for academic investigations over the lost or forgotten connections, mainly over historical facts over the last one hundred and fifty years—not quite the range of contemporary art production—and on points of encounters of both Chinese and Ottoman art and archaeology with that of Europeans, a comparative reading remains unattempted.

For A Twist in the Untimely, the Istanbul City pavilion of the 9th Shanghai Biennale, we decided to make a selection of three propositions that allude to the various ruptures and continuations that resulted within both contexts. We will collaborate with a group of strong artists whose work traces several histories and delineates several fault lines inherent in the Westernization process.

Please see below the three artists selected and their respective projects:

The Turkish opera diva, Semiha Berksoy’s life spans most of Istanbul’s twentieth century history, from the old Ottoman Empire to the most recent present. Semiha Berksoy was the first lady of Turkish opera as well as one of the most colorful figures in contemporary Turkish art. In addition to her career as a soprano, in which her heavy makeup made her a symbolic image in Turkish culture, she was known internationally for her paintings, which often depicted a little girl, a personification of herself.

She was asked to sing in the first Turkish opera, Ozsoy, in the presence of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey, who said he was stunned by her voice. In 1939, for the 75th birthday of Richard Strauss in Berlin, she sang the role of Ariadne in Ariadne auf Naxos, becoming the first Turkish prima donna to perform on stage in Europe.

Berksoy’s personal life reflected her revolutionary character, as she never hesitated to visit her lover, the celebrated left-wing Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet, in prison, despite the risk of being labeled a communist. She also appeared onstage in daring costumes, challenging traditional concepts of stage propriety and classical art. In a stage performance at the live music club Babylon club in Istanbul in November 2000, she joined a percussion group and performed in a wide spectrum of the arts—from poetry to singing to drawing to drama—in a transparent self-painted costume.

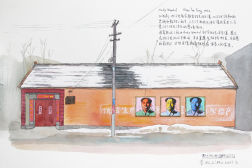

A Twist in the Untimely proudly features Berksoy’s paintings on bed-sheets along with a drawing by her based on Hikmet’s fantastic poem titled Gioconda and Si-Ya-U, about the love affair between Gioconda (Mona Lisa) and a Chinese student friend of Nâzım Hikmet’s, who is described to be “honey-tongued and almond-eyed.” The affair starts at the Louvre Museum in Paris and ends in Shanghai. In reality, Si-Ya-U is no one other than revolutionary poet and Mao Zedong’s high school classmate Emi Siao 萧三 (Xiāo Sān, also called Emi Xiao, 1896-1983). Hikmet memorialized Emi Siao in this 300-line poem, casting him as a dapper, fashionably dressed Chinese revolutionary in love with Gioconda (Mona Lisa), who returns his love. When Si-Ya-U returns to China and the revolution, Gioconda is impassioned and breaks free from her frame at the Louvre Museum to become a revolutionary herself.

On view is also footage and film materials, which include Semiha Berksoy’s performance, and her ruminations about her work on Nâzım Hikmet, the renown Turkish poet, playwright, novelist and memoirist, who was often described as a “romantic communist” and “romantic revolutionary,” but was repeatedly arrested for his political beliefs and spent much of his adult life in prison or in exile.

Elif Uras’ wonderful ceramic sculpture Janet (Mihrisah Sultan) is a life-size replica of an 18th century chair imported to the Ottoman palaces from France, around the time that Turks were moving from low seating cushions (sedirs) into the more Western chair styles. Titled after Mihrisah Sultan whose given name was Janet—the French-born wife of Sultan Mustafa III and the mother of Sultan Selim III, who ruled Turkey around the same time the chair first appeared in Istanbul—this realistic and precisely detailed and cracked, full-size glazed ceramic chair acts as a site for the fluidity of ideas and influences beyond time and borders. But mainly, the chair, which was modeled after the ornate furniture designed for a wife of an Ottoman Sultan, sheds light on the transition from tradition to modernity.

While Uras continues to reformulate the Turko-Ottoman tradition of Iznik (Nicea) in terms of content and form, she also examines the incongruity of the materials and underlining fragility of the on-going transitions within the nation-state infrastructure. Uras has become known for her treatments of the Ottoman tradition of Iznik Çini that started in the 15th century—the desire to imitate Chinese porcelain to create tiles and objects for the Ottoman palaces, hamams, mosques and homes of the bourgeoisie—which died after the 17th century, only to be rediscovered in late 20th century.

Historically, Iznik also reflected the male patriarchy of traditional society, with male artists producing work that adorned the walls of spaces limited to males, such as the male quarters of mosques and baths. Working as the resident artist at the Iznik Foundation for the past few years, Uras also makes note of how the gender roles are changing with respect to production, with more and more female artists dominating the studios today.

Annika Eriksson, who splits her time between Istanbul and Berlin, shot a film in Istanbul in 2010. Eriksson’s film, Great Good Place, hosts a carpet-like colony of domesticated cats in a park near the city center of Istanbul. The cats took it upon themselves to claim their territory within the public space, whereas constant change abounds around them, and the focus is mostly in the vertical rather than the horizontal. What is the secret that holds them together in the midst of the night, in the midst of Istanbul in this park? Cats are a bit like “ghosts,” telling of a constellation for a collective future, present or past, while the uncanny in the normality or the everyday is also present. Great Good Place, remains “a fertile site,” where positions against gentrification, a sense of community, notions of public exposure collapse, collide and allude to silent forms of resistance.

Without laying claim to any illustrative narratives or a simple description about Istanbul, the pavilion delivers a heterogeneity of voices—coincidentally of three women—and proudly presents itself at a time of growing interest in both cities. The cities are brimming with hype and promise: they could almost be considered heavenly places, able to alleviate the burden of the West. As a possible result, the curators cannot help but pose the question: can an exhibition as such, with metaphorical sketches, condensed and intense gestures in a designated pavilion ever be a final distillation in and of itself? Shouldn’t it be read only as an unfolding process in which various historical and artistically historical dynamics are triggered, prompted and reconstituted?